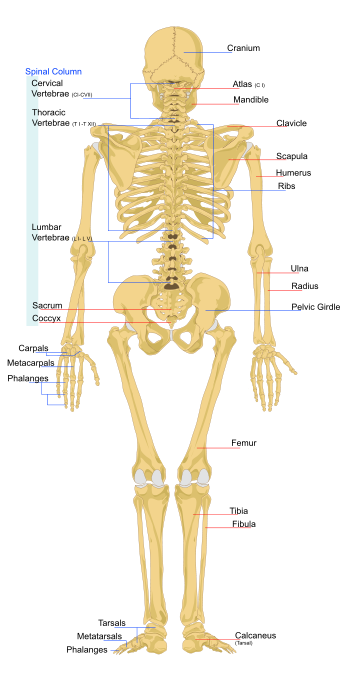

Human skeleton

The human skeleton consists of both fused and individual bones supported and supplemented by ligaments, tendons, muscles and cartilage. It serves as a scaffold which supports organs, anchors muscles, and protects organs such as the brain, lungs and heart. The biggest bone in the body is the femur in the upper leg, and the smallest is the stapes bone in the middle ear. In an adult, the skeleton comprises around 14% of the total body weight,[1] and half of this weight is water.

Fused bones include those of the pelvis and the cranium. Not all bones are interconnected directly: There are three bones in each middle ear called the ossicles that articulate only with each other. The hyoid bone, which is located in the neck and serves as the point of attachment for the tongue, does not articulate with any other bones in the body, being supported by muscles and ligaments.

Contents |

Development

Early in gestation, a fetus has a cartilaginous skeleton from which the long bones and most other bones gradually form throughout the remaining gestation period and for years after birth in a process called endochondral ossification. The flat bones of the skull and the clavicles are formed from connective tissue in a process known as intramembranous ossification, and ossification of the mandible occurs in the fibrous membrane covering the outer surfaces of Meckel's cartilages. At birth a newborn baby has over 300 bones, whereas on average an adult human has 206 bones[2] (these numbers can vary slightly from individual to individual). The difference comes from a number of small bones that fuse together during growth, such as the sacrum and coccyx of the vertebral column.

Organization

Much of the human skeleton maintains the ancient segmental pattern present in all vertebrates (mammals, birds, fish, reptiles and amphibians) with basic units being repeated. This segmental pattern is particularly evident in the vertebral column and in the ribcage.

There are 206 bones in the adult human skeleton, a number which varies between individuals and with age - newborn babies have over 270 bones[3][4][5] some of which fuse together. These bones are organized into a longitudinal axis, the axial skeleton, to which the appendicular skeleton is attached.[6]

Axial skeleton

The axial skeleton (80 bones) is formed by the vertebral column (26), the thoracic cage (12 pairs of ribs and the sternum), and the skull (22 bones and 7 associated bones). The axial skeleton transmits the weight from the head, the trunk, and the upper extremities down to the lower extremities at the hip joints, and is therefore responsible for the upright position of the human body. Most of the body weight is located in back of the spinal column which therefore have the erectors spinae muscles and a large amount of ligaments attached to it resulting in the curved shape of the spine. The 366 skeletal muscles acting on the axial skeleton position the spine, allowing for big movements in the thoracic cage for breathing, and the head. Conclusive research cited by the American Society for Bone Mineral Research (ASBMR) demonstrates that weight-bearing exercise stimulates bone growth. Only the parts of the skeleton that are directly affected by the exercise will benefit. Non weight-bearing activity, including swimming and cycling, has no effect on bone growth.[6]

Appendicular skeleton

The appendicular skeleton (126 bones) is formed by the pectoral girdles (4), the upper limbs (60), the pelvic girdle (2), and the lower limbs (60). Their functions are to make locomotion possible and to protect the major organs of locomotion, digestion, excretion, and reproduction.

Function

The skeleton serves six major functions.

Support

The skeleton provides the framework which supports the body and maintains its shape. The pelvis and associated ligaments and muscles provide a floor for the pelvic structures. Without the ribs, costal cartilages, and the intercostal muscles the lungs would collapse.

Movement

The joints between bones permit movement, some allowing a wider range of movement than others, e.g. the ball and socket joint allows a greater range of movement than the pivot joint at the neck. Movement is powered by skeletal muscles, which are attached to the skeleton at various sites on bones. Muscles, bones, and joints provide the principal mechanics for movement, all coordinated by the nervous system.

Protection

The skeleton protects many vital organs:

- The skull protects the brain, the eyes, and the middle and inner ears.

- The vertebrae protects the spinal cord.

- The rib cage, spine, and sternum protect the lungs, heart and major blood vessels.

- The clavicle and scapula protect the shoulder.

- The ilium and spine protect the digestive and urogenital systems and the hip.

- The patella and the ulna protect the knee and the elbow respectively.

- The carpals and tarsals protect the wrist and ankle respectively.

Blood cell production

The skeleton is the site of haematopoiesis, which takes place in red bone marrow. Marrow is found in the center of long bones.

Storage

Bone matrix can store calcium and is involved in calcium metabolism, and bone marrow can store iron in ferritin and is involved in iron metabolism. However, bones are not entirely made of calcium,but a mixture of chondroitin sulfate and hydroxyapatite, the latter making up 70% of a bone.

Endocrine regulation

Bone cells release a hormone called osteocalcin, which contributes to the regulation of blood sugar (glucose) and fat deposition. Osteocalcin increases both the insulin secretion and sensitivity, in addition to boosting the number of insulin-producing cells and reducing stores of fat.[7]

Sex-based differences

There are many differences between the male and female human skeletons. Most prominent is the difference in the pelvis, owing to characteristics required for the processes of childbirth. The shape of a female pelvis is flatter, more rounded and proportionally larger to allow the head of a fetus to pass. Men tend to have slightly thicker and longer limbs and digit bones (phalanges), while women tend to have narrower rib cages, smaller teeth, less angular mandibles, less pronounced cranial features such as the brow ridges and external occipital protuberance (the small bump at the back of the skull), and the carrying angle of the forearm is more pronounced in females. Females also tend to have more rounded shoulder blades.

Disorders

There are many disorders of the skeleton. One of the most common is osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a disease of bone, which leads to an increased risk of fracture. In osteoporosis, the bone mineral density (BMD) is reduced, bone microarchitecture is disrupted, and the amount and variety of non-collagenous proteins in bone is altered. Osteoporosis is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) in women as a bone mineral density 2.5 standard deviations below peak bone mass (20-year-old sex-matched healthy person average) as measured by DXA; the term "established osteoporosis" includes the presence of a fragility fracture.[8] Osteoporosis is most common in women after the menopause, when it is called postmenopausal osteoporosis, but may develop in men and premenopausal women in the presence of particular hormonal disorders and other chronic diseases or as a result of smoking and medications, specifically glucocorticoids, when the disease is craned steroid- or glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (SIOP or GIOP).

Osteoporosis can be prevented with lifestyle advice and medication, and preventing falls in people with known or suspected osteoporosis is an established way to prevent fractures. Osteoporosis can also be prevented with having a good source of calcium and vitamin D. Osteoporosis can be treated with bisphosphonates and various other medical treatments.

Gallery

Drawing the reverse of a female skeleton giving an impression of the location relative to surface markings |

Annotated skeleton |

Human skeleton on display at The Museum of Osteology |

References

- ↑ William W. Reynolds and William J. Karlotski (1977). "The Allometric Relationship of Skeleton Weight to Body Weight in Teleost Fishes: A Preliminary Comparison with Birds and Mammals". Copeia: 160–163.

- ↑ "Skeleton - Bone growth". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/science/humanbody/body/factfiles/bonegrowth/skeleton.shtml. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- ↑ Miller, Larry (2007-12-09). "We’re Born With 270 Bones. As Adults We Have 206". Ground Report. http://www.groundreport.com/Health_and_Science/We-re-Born-With-270-Bones-As-Adults-We-Have-206.

- ↑ "How many bones does the human body contain?". Ask.yahoo.com. 2001-08-08. http://ask.yahoo.com/20010808.html. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ http://education.sdsc.edu/download/enrich/exploring_human.pdf

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Tözeren, Aydın (2000). Human Body Dynamics: Classical Mechanics and Human Movement. Springer. pp. 6–10. ISBN 0-387-98801-7.

- ↑ Lee, Na Kyung; et al. (10 August 2007). "Endocrine Regulation of Energy Metabolism by the Skeleton". Cell 130 (3): 456–469. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.047. PMID 17693256. PMC 2013746. http://download.cell.com/pdfs/0092-8674/PIIS0092867407007015.pdf. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ↑ WHO (1994). "Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group". World Health Organization technical report series 843: 1–129. PMID 7941614.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||